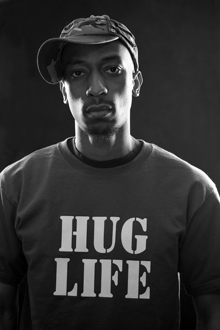

More or Les

By wavelength ~ Posted Tuesday, January 30th 2007

Sunday, February 1110:45pm @ SNEAKY DEE’S

Purveyor of: INDIE RAP FROM THE SIDEWALKS OF QUEEN WEST

More or Les, a.k.a. Les Seaforth, is a self-described “socially conscious” Emcee who recently put out the record The Truth About Rap. Kate Carraway talks to Les to find out what that truth is.

I understand your opposition to the materialistic themes in most mainstream rap, but don’t you think that rap should also be used as an outlet for people who are going through the shit that leads them to glorify or celebrate materialism? Isn’t “thug rap” just as socially conscious as “socially conscious” rap?

I agree that rap is often a portal into the common man or woman’s living conditions. As a matter of fact, I think it’s one of the elements of the genre that helps define it. However, I don’t find “thug rap” socially conscious — I find it to be a gimmick. To be specific, the title “thug rap” is a gimmick. That said, there is a bit of “gimmick” in every performer (including myself), but as a fan, I’ve always been more interested in the artists capable of presenting something of their own personality in their performance regardless of their level of social consciousness (as long as they have something interesting to say). Titles like “thug rap” or even “socially conscious rap” are the extremes and rarely convince anyone of having true value. I believe you can have the message without the stereotypically defining “boxes” to slot people into.

You co-wrote a whole chapter in uTOpia [The State of the Arts: Living with Culture in Toronto, the second installation in the “uTOpia” book series] about how rap in Toronto isn’t given much exposure and how the rappers that do get a lot of play are more easily digestible or, like k-os, are basically adult contemporary artists. What will it take for the media and audiences and the industry in Toronto to be as excited about and committed to rap as they have been to indie rock?

The answer comes back to the point Jill and I were trying to make in our essay: it will take infrastructure that currently does not exist to get rap audiences, artists, media and the industry more excited. Things like venues dedicated to presenting talented, consistent acts on a regular basis. Industry believing — and working towards the goal with the artists rather than in spite of — that Canadian hip-hop is a viable money-maker. Media and industry working to present more than the required percentage of CanCon to audiences. Artists determining every way possible to get to the fans with cool web sites, intriguing blogs, kick-ass live performances, dope ring tones, amazing busking — any and every interesting way to get the word out. With all the required parties actively and enthusiastically participating, I think things can and will “fall into line”: with the word out on amazing acts and a venue promoter looking to fill his bar with drinking hip-hop heads who are dedicated to see the “local hero doing good,” you’re guaranteed to get a fantastic synergy.

In the last year, WL has tried to bridge gaps between different art diciplines, but it seems like there isn’t much crossover, especially in regards to art and race, which is weird considering Toronto is touted as such a diverse city. Do you think that’s a relevant observation?

From my own observations, there is some intersection between music and the art community in Toronto, but as to whether or not that’s minimal due to racial divides, I’m not sure. From it’s beginnings in New York, aspects of the hip-hop culture came together that were music and art community intersections that moved beyond racial divides (though not easily at first) like members of the Rocksteady Crew with (visual) artists Rammellzee, Fab 5 Freddy, Keith Haring and some early local emcees. But with hip-hop these days, I think it’s just not in your average Emcee’s mind to “rap at an art show”—on either a grand scale or in their community. Locally, Emcees may not perceive it as part of their world, and corporations working with the arts community is a partnership that has always been “strained.” Disinterest from the musicians themselves could make it even more so.

By Kate Carraway