Music, arts and gentrification

By wavelength ~ Posted Tuesday, January 30th 2007

By Stuart Duncan

The indie music and arts scene in Toronto has a common lament — that downtown has become a place where we can’t afford to be. Rising rents shift us out of our familiar neighbourhoods, and our tiny stores, venues and galleries are gobbled up by condos and upscale retail development. We curse the commercialization of our former haunts, but what role have we played in the gentrification of these spaces?

In Toronto, as in most large urban centres, artists and musicians are part of cycle of cultural transformation, where the search for affordable places to live and work leads to the creation of artist enclaves in traditional working class neighbourhoods. This migration often makes neighbourhoods more attractive to developers, and upscale development displaces local shops and residents.

“There are lots of gallery owners who will gravitate to a particular area because there are lots of artists working in that area and you can turn it into a gallery district,” states John Lorinc, author of 2006 urban affairs book The New City. “Then you get people who like to buy expensive art coming in there and they know a guy who develops condos. Then people who have the means to buy a $400,000 semi say ‘I like living near galleries, that is pretty cool.’ ”

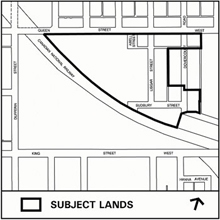

Be it in the Annex, Yorkville or what we see currently in West Queen West, Toronto’s emerging arts and music communities are often a catalyst for this type of development.

“I think that there are some artists who are complicit in gentrification practices without even knowing what gentrification is or the impacts of their actions,” states urban planner Susannah Bunce (sister of Wavelength’s Jonny Dovercourt). “Cute boutiques, cafes, quirky collector stores, galleries, juice bars — these are all stores that artists probably frequent more than the average working class guy, and these are the types of stores and services that, once multiplied, can lead to a distinct change in character of a neighbourhood. Here, the artist’s eye for design gets rid of the shabbiness that is typically equated with a ‘run-down’ neighbourhood, and by doing so, aids gentrification practices.”

But how do we work to fight against our role in the cycle of gentrification? Bunce believes that as an arts community we need to work to stop the impact of rising rents and costs of living in the downtown core. She cites policies of limiting the ability to rezone areas and caps on commercial rental rates as simple examples of what can be done to slow the rapid gentrification of traditional neighbourhoods.

Adrian Blackwell, artist and urban and architectural designer, believes we need to return to period of a greater discourse on the politics of art. “In the 70’s, when artist run centres like YYZ, A Space and Mercer Union were being created, there was a real political dialogue about what was happening. There was action around the problems of the arts community, its whiteness, its affluence and there was a lot of radical politics within it.”

When I ask Blackwell why he claims the art community has become more apolitical he responds, “The encroachment of the market and the gallery system has exponentially expanded in Toronto since the 80’s. There is this much wider net of market-driven institutions, people think they can make it big at any age, there are advantages in that it makes the youthful art scene more dynamic, but it really depoliticizes it.”

Like the art scene, indie culture has become increasingly entwined with big business, market-driven forces are infiltrating underground culture, and a scene that used to be about exciting cultural and social action is increasingly used to generate income. It is important for us to confront artists and spaces that are complicit in the commodification of culture and public space. We shouldn’t be afraid to say it’s shitty how the Drake continues to affect West Queen West and demand that our peers not play or support such a place.

As a group, musicians and artists have a lot of privilege, we have access to spaces and resources — be it photocopying, media contacts, bookers — that most of society doesn’t, and we need to do something with that privilege. The pool of creative skills that we have as a group is amazing, but we need to use it more to affect political change. We have to break out of the model of just throwing fundraisers for political causes and actively participate in those struggles, on a day-to-day basis and at grassroots level.

The Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC) in Brooklyn serves as an inspirational example of what Torontonians could to do preserve the character of their communities. Like many neighbourhoods in Toronto, upscale residential development was forcing many long-time residents to leave Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighbourhood. In response, the FAC declared 105 square blocks of Park Slope a Displacement Free Zone. When the FAC receives a request for assistance from a resident facing eviction, the committee works to fight the eviction and mobilize the community. In most cases, with the help of the FAC, landlords and tenants have been able to reach fair settlements.

The music and arts communities could be active participants in similar campaigns in Toronto. It is not difficult to find common struggles with the people around us — development that drive venues and gallery spaces out of a neighbourhood also force low income tenants and shop owners to find a new home — but we have to leave our comfortable scenes to do it.

“One of the really crucial things is that we think of the city more broadly. One of the problems is that certain arts communities that have access to certain media, are located in a certain space on the downtown west side of Toronto — then that becomes the subject of discussion,” Blackwell states. “The effects of gentrification are no longer just on the west side, the effects of the problem are felt across the whole city. We have to think creatively about how to not just access communities that are approximate, but how to think of Torontopia at a larger scale.”